Returning to writing, after a long absence. At the end of last season, my head was full, and I needed to focus on wrapping ‘Corsair’ up. As you can see its taken a few weeks for me to feel like writing. Anyway.

I’ve previously stored ‘Corsair’ at Upton, during the 2009/2010 winter.

When that season had ended, I’d just learnt about the ‘Cruise of the Clipper’ – those of you interested can look here; https://broadssailing.blog/2019/11/18/cruise-of-the-clipper/

That year, I sailed ‘Corsair’ to Upton from her Oby mooring in late December, she was due to be lifted just before Christmas. It proved to be the only time I’ve sailed her in the SNOW, and to be honest it felt very intrepid (bl&%dy cold) when I’d reached Upton.

A few days after she’d been craned – Upton froze rather spectacularly!

In 2009 – when I worked on the boat, I’d live on ‘Corsair’ at weekends. Luxury it wasn’t! Sleeping inside 2 sleeping bags, having first made the boat utterly disgusting by filling it with dust, etc!

It embarrasses me now, but looking back through notebooks I can see that during that winter a repair (!) was inflicted to the port side-deck which leaked.

It involved removing the cant-rail, and then carefully peeling back the trac-mark. I hadn’t money to buy new! Then, very carefully I dug out the rot, and the soggy bits… being VERY careful not to go through the boards completely. Then I sprayed everything with cuprinol wood hardener, before literally trowling epoxy in and smoothing it out.

Inside the boat, a mixture of masking tape and playing cards were sacrificed to stop the epoxy from leaking through… (!!!)

I also had to complete my 1st replacement plank. I made about every mistake I could have made. The plank was short (about 4ft), was butt-jointed to the adjacent timber with some good old ‘prayer books’ on the inside, and I think I used a linseed based frame sealant to caulk up.

Also – in view of my ‘ahem’ limited budget – that plank was fashioned from a 5ft length of 7 inch wide skirting board… If you cut the moulding off, you can just about get a short plank out of it (!)

I can’t defend these repairs today, as they were short-lived. But at a time when I was struggling financially, they meant I kept the boat afloat and sailing.

Thankfully no pictures exist…

And, having suitably disgraced myself, I will try and explain the connection between Upton and Chumley & Hawke…

Eastwood Whelpton boatyard was founded by Tim & Annie Whelpton. Tim having built ‘Clipper VI’ in 1951, we met him by chance during 2008; https://broadssailing.blog/2019/06/20/cruise-2008-days-4-5/

One of the post-war owners of Chumley & Hawke, Vic Harrison evidently supported Tim & Annie’s endeavour to run their own hire fleet. When they moved to Upton in 1958, it was in the midst of changes at Chumley & Hawke.

I understand that Vic was instrumental in Tim & Annie taking a number of the C & H yacht fleet with them;

– Reveries 1 – 6 (Press built)

– Brown Elf, Imp and Sprite (C&H built – ALB designed)

– Pixie (Press built)

R/e the builder’s notes above… I know they’re accurate in terms of ALB designs.

I’m not clear when the Reverie’s joined C&H, but given they are Press built boats, and Alfred Yaxley (the post-war foreman at C&H) came from the Press yard, I suspect the boats came with him post WW2, so to speak.

In fact, all these yachts were 2 berth, small yachts. Leading to the nickname that EW was the ‘honeymoon’ fleet!!

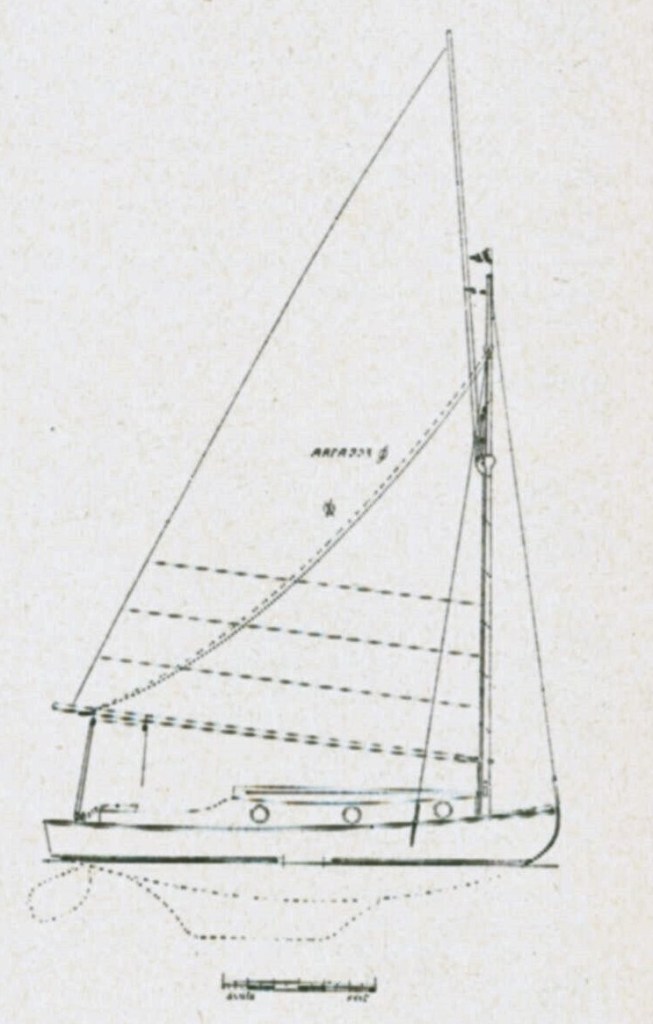

Design- wise, the Brown Elf class was the most interesting in the EW fleet at that time. They really show A.L Braithwaite’s tendency to experiment.

Originally these were ‘Una’ rigged, in the same way a ‘catboat’ is in the US. It certainly wouldn’t be the first instance of US design influencing boats on the Broads, its rumoured a local boatbuilder (from up Wroxham way!) used the ‘Rudder’ magazine as a source of inspiration!

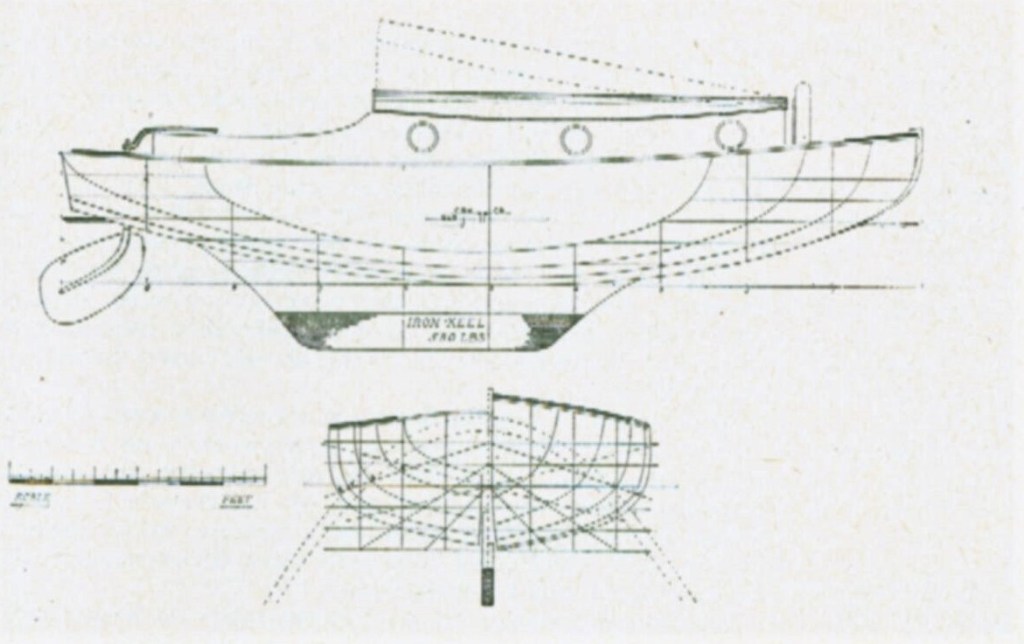

They are diminutive – vital statistics; 20 LOA, 17ft 3″ LWL, 7ft 6″ beam, with 3ft draft and 223sq. ft of sail & 580lb of external ballast.

Interestingly, Braithwaite wrote to Yachting Monthly in 1949 about the Brown Elf class – they were designed by him in 1930, and must have been one of his 1st designs for C&H.

Their rig differed from a typical gaff Broads yacht, not just with the lack of jib, but also that they carried jaws on the boom, and a down-haul to tension the luff. Much like a lugsail dinghy, although you could argue given their size, Brown Elf, Imp & Sprite were little more than half-deckers (in the nicest possible way).

The Una rig would have made alot of sense for a Broads hire-boat, it locates the mast well out of the way of any accomodation. There’s minimal standing & running rigging. and of course in a moment of panic, if the helm is abandoned they should luff & come to a halt.

Most sailing yachts in hire operated on that same principle. A large mainsail with weather-helm was considered safer with inexperienced sailors.

Happily, unlike the ‘Clippers’ there are lines plans which have been replicated for the Brown Elf class, and you can really see the metacentric theory being applied, look at the area curves, and how uniform they are.

It certainly looks like the maximum underwater sectional area is absolutely 50% along the DWL.

Once the Brown Elves were rehomed at Upton, it wasn’t long before Tim also took to altering them. The cabin’s were extended forward, and the Una rig abandoned for a Bermudian sloop configuration.

As a nice circuitous touch, here’s a photo of Brown Elf in 1962, outside Horning Ferry, whose link to C&H was the tragic demise of Joseph Lejeune, foreman.

I’ve no doubt that Lejeune oversaw the building of the Elf’s, at what must have been an exciting period in C&H’s history – a new owner, new designs and minor publicity in yachting press of time.

Anyway, I hope I’ve managed to narrate the link between Chumley & Hawke, Tim & Annie, Upton, and ‘Corsair’s’ history.

Goodnight.